Thank you all for waiting during my unexpectedly long hiatus. I think you will find that the wait was worth it, as I have a handful of good-length articles nearly ready to publish. A further note about this article: Montessori theory and practice are so vast and complex that an article that even scratched the surface could not fit into one post without dragging on too long. For that reason, I have split it into two parts. The first part covers the origins, principles, and methods of Montessori education, while the second part will cover the aims and analysis of what is useful and not useful in Montessori. Even then, I can only provide a sample in this essay but that sample is fascinating enough on its own. Enjoy.

Introduction

Some time ago, I wrote an article on the industrialization of education. At the end of that essay, I committed to writing a series of posts on educational theorists who “rebelled against the machine” and tried new ideas, for good or bad, so that we could explore alternatives to a slowly dying system. To simply complain about “cells and bells” public education will neither accelerate the glacial pace of its decline nor produce good alternatives. What I advocate for is a distinctly non-denominational approach to teaching: use what works for your particular children and circumstances, discard what does not. In the prior article of this series, I talked about Ella Fratau and her forest school movement. I described the strengths and weaknesses of that program from the perspective of a prospective homeschooler, microschool teacher, or private school educator a set of ideas to borrow from for their own program. With this current article, I risk peaking early, but the subject is simply too interesting and too large for me to resist. While I am not an orthodox Montessorian, I believe any educator will find many useful things in her system, particularly in the fields of math, geometry, and ELA. There are, however, some issues with her theories outside those subject areas, and those will be a topic in the next article.

Origin and Overview

Maria Montessori was an Italian physician born in 1870 to a well-off but not aristocratic family, and her life story has unfortunately been elevated to hagiography by many of her followers. Suffice it to say that Dr. Montessori was known as an excellent student and chose to go against the current cultural mores to become the first woman to be licensed as a doctor in modern Italian history. She was evidently quite talented. Dr. Montessori gravitated toward working with children with severe disabilities, who at the time were confined to asylums. The asylums in those days were dark, miserable, and at times even evil places. The children spent their days in large, cold rooms whose only furniture was rows of benches along the walls, without toys or education of any kind. Feeling compelled to try something different, Maria Montessori taught herself French so she could read the work of Piaget and Sequin, two revolutionary researchers on child development and the education of disabled children. Dr. Montessori used their ideas as a basis to make educational materials for disabled children and had success. After working with these materials, they were able to test as well as non-disabled children on state exams. Sometime later, she was asked by a slumlord in Rome to run a school for local children to keep them from damaging the remodeling that was being done on his tenement buildings and provided a space for the purpose, but little money. The children’s parents were factory workers who were too poor to afford childcare, and the children themselves were too young (between 2 ½ to 6) to attend state schools. This is when the famous “Montessori Miracle” took place. She asked parents and friends to make furniture for the school, which due to funds ended up being regular house furniture, but smaller. This first school was called the Casa de Bambini (“Home for Children” in Italian). Without textbooks or papers, they used her ever-evolving roster of didactic materials. Dr. Montessori herself stated that what exactly happened in that school “would forever be a mystery to [her]”. Children who had before been rowdy, frightened, angry, and confused became calm and hardworking. An almost eerie calm fell over the classroom. The children seemed utterly absorbed in what are now the classic lessons of a Montessori “primary” classroom: the knobbed cylinders, the pink tower, dressing frames, water pouring, and table washing. Moreover, the children became eager writers and spellers with the sandpaper letters and moveable alphabet. “The Montessori Miracle” became an international sensation, visited by top politicians, foreign dignitaries, and other notables. A “glass classroom” was built for the 1915 World’s Fair in San Francisco, where the public could freely see how a Montessori classroom worked. The stories of the first Casa de Bambini and the “glass classroom”, along with Maria Montessori’s own words, function as a kind of New Testament or Pali Canon for the movement

Dr. Maria Montessori

Today, there are over 15,000 schools that claim the mantle of Montessori, with the lion’s share of them being in the US, Canada, western Europe, India, China, and Thailand. A growing number are publicly funded in one way or another. It is ironic then that a movement so well-funded is also so mysterious, even amongst those who engage in political commentary on education (a trait shared with its kissing cousin, Waldorf Education). With the context and background taken care of, let’s look at the fundamentals of Dr. Montessori’s ideas and a sample of her materials and methods.

Principles

The first principle is that Montessori proposed a theory of infant and child development that is split into two principles phases. The first one lasts from birth to age 6, and the second goes from around age 6 to 12. Adolescence is a separate phase and ends at age 18. In the first phase, the infant and child possess what Dr. Montessori called an “absorbent mind” that drinks in the world around them and yet is still governed by its internal laws for growth. Dr. Montessori was not a “blank slate” theorist of human nature. Children at this age are most easily absorbed into kinesthetic activities and require physical objects to manipulate to understand concepts like numerical quantity, physical size, and the alphabet. In the second phase, the child has shifted to having a “mathematical mind” that is capable of greater abstraction, becoming less reliant on kinesthetic materials, and also seeks to find order in the world around them. Children at this age want to know where the world originated, plants, animals, and history.

The second principle is that the most efficient classroom is one that is based on didactic materials, an open work period, and is as similar to the home as possible. These are pictures of a typical Montessori classroom:

You will notice that there are no rows of desks and chairs. There are available tables, but children commonly work on the floor with rugs for the materials to rest on. Whole class lessons are the exception in Montessori, but not uncommon. Instead, the teacher rotates around the room observing, providing individual help, and giving lessons that typically include anywhere between 3-6 children. These lessons last between 5 to 15 minutes and are usually instructions on how to use a didactic material. The materials have what is called “control-of-error” and are either self-correcting or come with an answer key. The furniture in a school closest to Dr. Montessori’s vision is plain, unpainted hardwood, with few decorations on either the walls or shelves, as she believed that too many posters and such overstimulated and distracted children. The materials have similarly muted colors. The work period in most Montessori schools is between 2 hours 15 minutes and 3 hours. The children may work on whatever they’d like, either for the day or for the week. Which is to say, some schools ask children to work on all their subjects over the course of the week, and others require that children work on every subject every day, but in more or less any order they’d like. A child in the former type of school may choose to work on math all day if he or she wants. Montessorians believe that such a framework encourages the child to concentrate because he or she is allowed to follow their greatest interest i.e. developmental need at any one time. Montessorians believe in avoiding interrupting children if at all possible and allowing the materials or answer keys to correct the children.

The third key principle is that Montessori education believes one should start with the big picture and then work down to the details. The long lessons in a Montessori classroom are stories told to the children that act as creative explanations for certain principles of grammar, mathematics, science, and history. The longest of all are called “The Great Lessons”, which are the Big Bang i.e. the birth of the universe, the coming of life on earth, the coming of human beings, the invention of spoken language and writing, and finally the invention of numbers and mathematics. These are told in grades 1-6 and have their own materials and assignments associated with them. Montessorians call this “Cosmic Education.” More on that in part two of this analysis.

The fourth key principle is that Montessorians avoid external rewards. They believe that all the work in their classrooms is specifically chosen to fit childhood development. Children are designed to learn how to read, write, and do mathematics and are naturally curious about the natural world and where it came from. If a child needs to be bribed into doing something, then it is probably being presented in a manner that is either developmentally inappropriate or simply not worth doing at that age. Since grades are a kind of external reward, they are avoided unless required by law. Sticker charts, points, PBIS, and other such behavioral management methods are also avoided unless they are part of a disabled child’s special education plan. This is more of a guideline than a hard rule for most, and most Montessorians will admit that at some point they will resort to forcing a child to learn to read, write, and do math.

Materials and Methods:

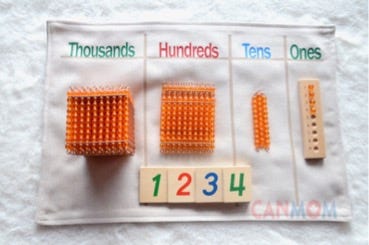

Let’s take the time to examine Montessori materials in math and in ELA (or “Language” as Montessorians call it) to get a sense of how they achieve what Montessorians called “materialized abstraction.” In math, the foundational materials are the golden beads: Here the beads come in the form of a single bead, called a unit, ten bars, hundred squares, and thousand cubes. To add and subtract with this material, they are placed on a mat that is color-coded: the unit section is green, the tens section is blue, and the hundreds section is red, and the pattern repeats for the thousands and millions “families.” You can see that multiple cues are used to reinforce the nature of quantity and value: physical size which is precise and proportional, color coding, numerical symbol, written word, and placement from left to right. All are necessary for the child to understand the mathematical process and speed the advancement to “pure abstraction” when math is done solely with numerical symbols and place values on paper.

Golden Beads and Mat

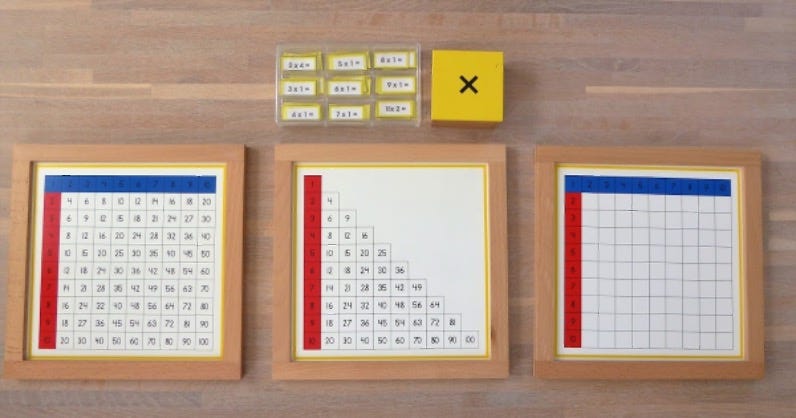

Another is the “finger charts” used to learn math facts. There are wooden tiles for the answers to put on the blank chart, and little cards that have the math problems on them so the children can write them down in notebooks.

Multiplication Finger Chart

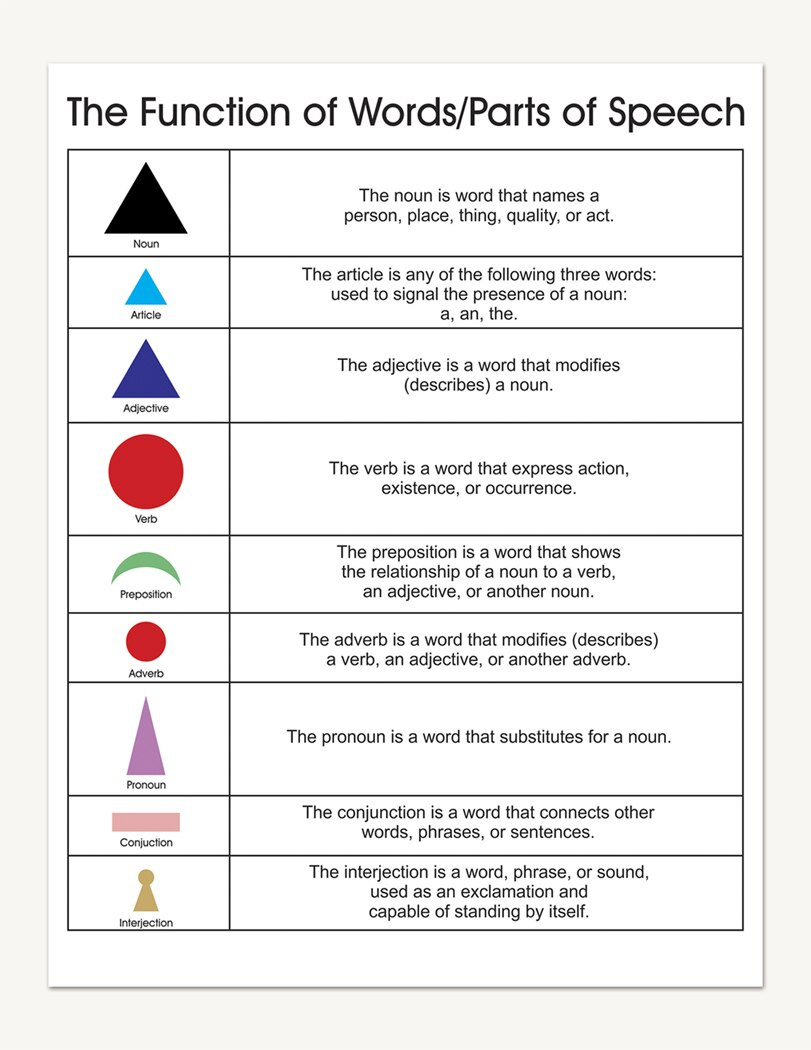

Next, we have “Language”. Montessori teachers for grades 1-6 teach grammar through a series of symbols, see below:

There is another more advanced set for students in grades 4-6, which has unique symbols for things like intransitive verbs, abstract nouns, etc. Montessori teachers will have stories and lessons where they explain the logic for each symbol. For example, nouns are large black triangles or pyramids because “they are the solid foundation of the sentence”, while verbs are red balls because “they have the energy in the sentence.” These symbols are used to “parse” sentences, as well as through an array of task cards and examples that are copied down in notebooks:

Finally, another rather unique and important aspect of Montessori education is that its curriculum for reading is based on phonics. Cueing strategies like those pushed by “whole language” and “balanced literacy” theorists such as Fountas and Pinnell and Lucy Calkins are not used, or at least they are not standard. The first of the several materials that do this come in the preK and kindergarten class (called variously “The Children’s House”, Casa, or “primary.”), the “color series.” Below are the "pink” series that teach CVC words (consonant-vowel-consonant) with short “a” vowels:

While there are pictures and occasionally objects that accompany the word lists, these are done for the sake of definition, rather than to guess the word’s pronunciation in the context of reading. These words are written and practiced either with a moveable alphabet of individual wooden letters or written down in lists. Word lists like this progress all the way up in graphical complexity to digraphs and trigraphs and in phonemic complexity to diphthongs and triphthongs.

. The Moveable Alphabet

These materials are taught in short, intense lessons of direct instruction interspersed among longer periods of independent work where the children use answer keys to check their work. The children are assessed by having them use the material in front of the teacher without the key or with a paper test. In the later elementary years, independent projects done based on chosen resources (books especially), become more common. Computers are rare overall until one gets up to the adolescent years, and tablets are restricted or absent.

Conclusion

When examining the principles, practices, and materials of Montessori, a clear intent is revealed: to allow the child to navigate a curriculum with a greater degree of independence than would be possible in most other systems (at least for a plurality or majority of children). The materials and the curriculum are highly structured, linear, and designed to be used in an environment with relative choice. The content of the materials in the “primary” classroom is 60/40 in its division between life skills and academics. The elementary classroom more heavily favors the latter. This culture has ramifications for what types of children are best suited to Montessori, and what types of adults it is capable of cultivating. We will examine that in greater depth in part two of this series on Montessori.

Thank you for coming to my lesson today. Class is dismissed.